My Blog

What does it mean to be civic-minded?

Over the past year or so, I’ve been changing the way I talk about myself and my work. Whereas before, I’d generally say that I’m a designer or email marketer, I’ve taken to calling myself a “civic-minded marketer, writer, and designer”. My day job is all about marketing and teaching others to market effectively, usually through writing and design. But what about the first part? What does it mean to be civic-minded?

Back in November, I published an article that attempted to define the word civics. After looking at the history of the word and a few popular definitions, I decided to define civics as:

Learning not only the science and systems of government but, more importantly, how we can all take responsibility for our collective actions and improve our communities as a result.

Most people think of civics as a subject taught (or formerly taught) at school, or something politicians do. But really, civics is about all of us interacting with our communities and trying to make those communities better.

So, for me, being a civic-minded anything means taking that to heart and thinking about how all of your actions affect those around you. It’s about taking responsibility for what you put into the world and trying to a make it a better place through your work—regardless of what your work actually is.

When it comes to marketing, writing, and design, I practice being civic-minded by:

- Making sure my work is as accessible and inclusive as possible.

- Using my platform at Litmus to promote diverse voices and good work.

- Volunteering my time, skills, and money with organizations working to improve our communities.

- Generally thinking about how my work fits in with the modern world.

Essentially, I’m learning to think of civics as less of an academic pursuit and more of a lens through which you view things, as well as something you practice constantly.

I think that everyone can—and should—become more civic-minded in their own work and lives, too. Not everyone has the luxury and privilege to pursue civics education in their free time or throughout their day, but even by asking the question, “How does this affect others?” we can all practice being civic-minded and help create a more equitable world in the process.

What is civics?

We’ve heard the word in school or rolling off the tongues of politicians. But what does “civics” actually mean?

Civics is a word most of us have heard growing up. In school, you either had a civics course of some sort or heard it floating around in social studies or history class. It crops up during campaign season and in the lyrics of Hamilton (“A civics lesson from a slaver? Hey neighbor, your debts are paid ‘cause you don’t pay for labor.”). But I never took the time to think about—let alone investigate—what “civics” actually means.

We’re trying to figure out what a word means, so let’s start with a dictionary definition. The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 5th Edition, defines civics as:

The branch of political science that deals with civic affairs and the rights and duties of citizens.

That’s a bit stodgy though, isn’t it? I much prefer this one from Wiktionary:

The study of good citizenship and proper membership in a community.

Sure, civics—as we’re taught in school (if we are taught it in school)—is about the science and mechanics of people’s interactions with the government. But it feels like it should be about so much more than that. It should be about how individuals participate in their community.

If we go back even further, we can see that the Romans certainly thought so. The word civics actually comes from the Latin civicus, which was that having to do with citizens, towns, or cities. Romans had a special honor for people who saved a fellow citizen’s life. They were bestowed a civica and the right to wear it. It was a crown of oak leaves and acorns that would probably fit right in at Coachella. Ever see one of those busts of a Roman emperor? It’s what he was wearing.

Not everyone in Roman life was given a civica, just those who were being good citizens and members of their community. Granted, that was usually during the course of fighting a war, but it seemed to focus on the active participation part which nowadays seems to go overlooked beyond voting in elections every few years.

All of that begs the question: What is a good citizen?

There are a lot of potential answers to that question, especially considering where you fall on the political spectrum. But to me, a good citizen attempts to do the following:

- Understand the responsibilities of citizenship.

- Look out for their community and its members.

- Actively participate in the process of government.

- Understand and accept the results of their actions.

There are lots of ways this can play out and it should be obvious to anyone paying attention to the world that being a good citizen is increasingly difficult in 2020.

Not everyone has access to education, let alone an education that teaches civics and the mechanics of government. Not everyone has the resources (like time and money) to give back to their community, especially given pandemics, police brutality, economic rollercoasters, and everything else that’s vying for our attention on a daily basis. And, with all of the gerrymandering and voter suppression that’s happened the past few decades, not everyone has a way to exercise their civic duties and participate in the process of government.

It’s hard and it’s only going to get harder. But it’s on each of us individually to take responsibility for being a good citizen and do what we can, where we are, to create a better community for everyone in that community, not just ourselves.

Which brings us to that last point—accepting the results of your actions in civic life.

There’s another concept related to all of this that comes from a more recent source: Sudbury schools. Sudbury schools are democratic schools that began in 1968 in Sudbury, Massachusetts. They’re founded on the belief that people need to learn democratic values and social responsibility by actually engaging in them, not just reading about them. Sudbury schools focus on three freedoms:

- Freedom of choice

- Freedom of action

- Freedom to bear the results of your actions

If Americans love one thing, it’s their freedom to act however they want. But what seems to be lacking is their duty to bear the results of those actions. Instead of being held accountable for predatory lending and financial meltdowns, Wall Street walks away with billions in bailouts. Officers of the law regularly murder Black people and walk away with their jobs and pensions intact. Some of us choose not to wear masks in public while complaining about continuing lockdowns and surges in COVID-19 cases. It’s pretty messed up, to be honest.

So, if I were to go back to that original question of what does “civics” actually mean, I’d say:

Learning not only the science and systems of government, but, more importantly, how we can all take responsibility for our collective actions and improve our communities as a result.

It’s not easy. We shouldn’t expect it to be. Our country is only getting more crowded and more diverse. But it’s work worth doing so that we can find a way for everyone to participate in its history while feeling safe and valued.

You Won’t Find Email Writing Here Anymore

Many of you know me from my work as an email marketer, designer, and developer. If you’re reading this, there’s a good chance it’s because you’ve learned about email from my books or videos or read, watched, or listened to my work at Litmus.

I used to blog here about email all the time but, over the last few years, have pulled back significantly from posting about email. That’s mostly due to the fact that I’m busy at Litmus and all my email energy goes into things like blog posts, ebooks, webinars, the podcast, etc. over there. But it’s also because email is only one of my interests—which is why recent posts have focused more on politics and personal stuff.

This is just a quick post to tell you that you can expect that trend to continue.

From here on out, don’t expect to find email-focused writing on my personal blog or in my newsletter.

That’s not to say that I’m not writing and teaching about email marketing anymore. I do that all day, five days a week professionally. Just don’t expect it here.

You can follow my work at Litmus for anything email-related instead.

I’m going to use my personal space here to explore other topics like design, politics, illustration, coding, music… all the things I love learning about outside of email marketing. It’s my personal website, so I want it to reflect my personality and interests.

So, if you’re here expecting more email marketing thought leadership, there are better places to go. If you’re cool with learning about other stuff from me, that’s fantastic. I’m glad you’re here. Keep up with all that other stuff by subscribing via RSS or signing up for my email newsletter (that won’t be about email anymore).

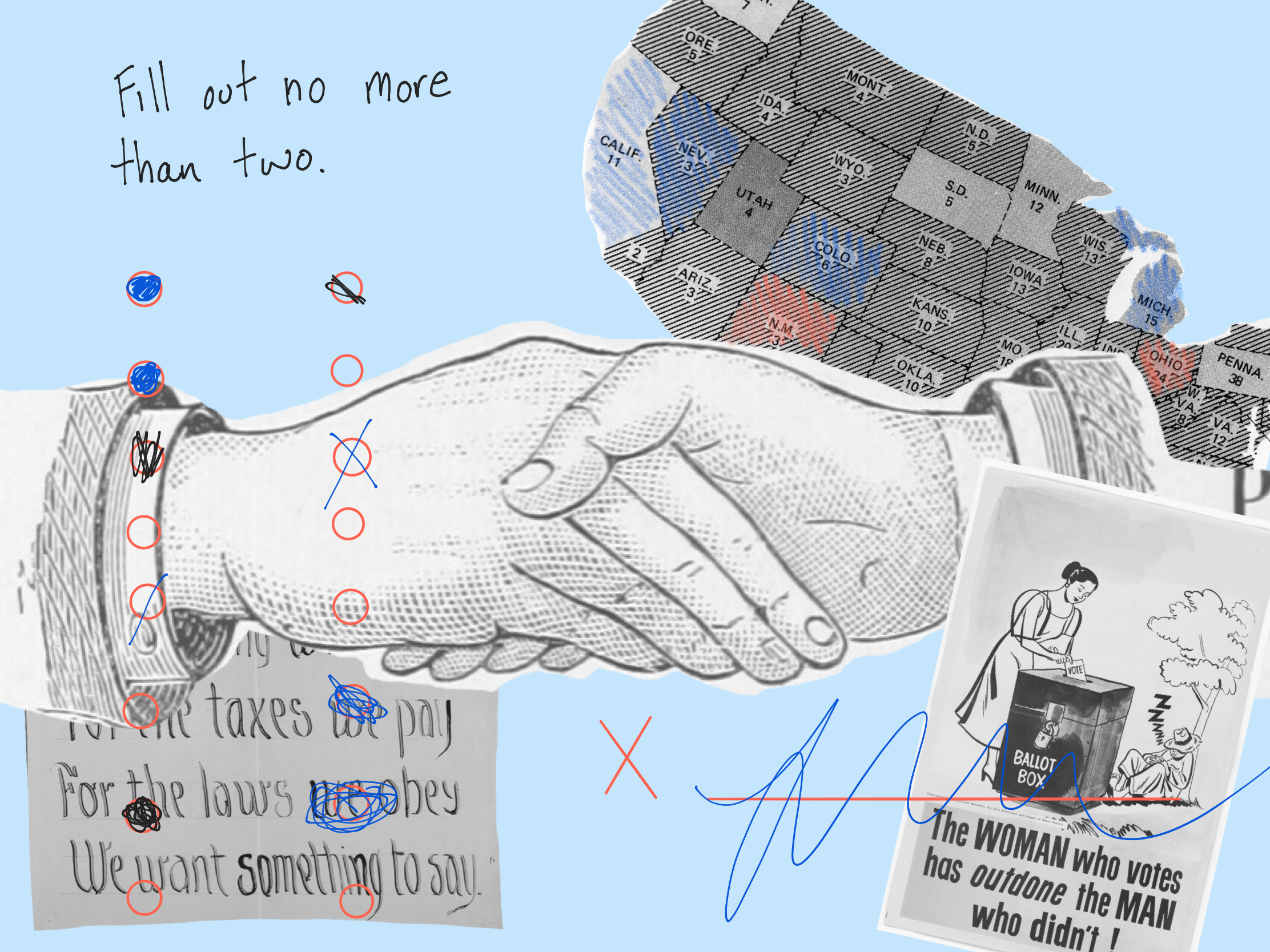

Adjudication

On Tuesday, November 3rd—Election Day—I woke up at 5:30am, showered, got dressed, and drove a cold mile to the Livonia Senior Center where I joined a group of dozens of volunteers to help run the 2020 election.

24 hours later, I was (thankfully) back in bed.

What happened during that 24 hours? Adjudication, of course.

What is adjudication?

Put simply, adjudication is the act of passing judgement on something. Although adjudication happens throughout various areas of law, in the case of an election, adjudication means something special.

It’s the process by which citizens judge ballots that were rejected by electronic ballot machines to determine:

- Whether or not a ballot—or parts of a ballot—can be counted.

- What those votes actually count towards.

It’s terribly consequential work and helps ensure that as many votes as possible can be counted and, if they can, are counted properly.

How does adjudication work?

Adjudication is a new process in our city, first implemented in the 2020 primary back in August. Before adjudication, if ballots were rejected by the electronic ballot machines, those ballots were spoiled wholesale and no votes were recorded.

With the introduction of adjudication, though, fellow citizens can help determine why the ballot was rejected, if it can still be counted, and what those votes go towards.

When you go to your polling location and vote in-person, your ballot may be rejected by the machine. But, since you’re physically there, you can spoil it, grab a new one, and get your vote in without too much trouble. For those voting absentee, they don’t have this luxury. Since they are not present when their ballots are counted by the machines, they can’t fix any issues to ensure their votes count.

Hopefully you can see how important adjudication is, then. Especially since damned near everywhere around the country saw record numbers of people voting by absentee ballots.

In Livonia, absentee ballots totaled around 45,000. That means, that starting around 6:30am on Tuesday, volunteers had to pre-process, sort, submit, adjudicate, and account for all 45,000 of those ballots.

Yes, it took a full 24 hours to process 45,000 ballots. 24 hours with dozens of people foregoing work, school, election updates, time with their families, and sleep. Keep that in mind the next time you get frustrated at how long it’s taking for counties to release vote totals.

The process by which it all happens is slow but pretty cool.

Ballots were brought in by the City Clerk, Susan Nash, and her staff. Livonia citizens then sorted ballots by precinct, sliced open all of the security envelopes, unfolded the ballots, and bundled them in stacks of (I believe) 25 ballots.

Those ballot stacks were then brought to one of six electronic ballot machines, depending on the originating precinct. Trained volunteers and staff then fed those ballots through the machines, clearing any jams and addressing any issues as needed, before packing each stack in secure lock boxes provided by the city.

If, for whatever reason, the ballot machine couldn’t determine who voted for what on any particular ballot, the ballot was sent to one of three adjudication stations which consisted of a vertical computer monitor loaded with custom software purpose-built for judging those ballots. The adjudicators would then review scans of each ballot, determine whether or not specific sections could be counted, and manually input the correct votes (or rejections) on a per-ballot basis before submitting the final ballot for counting.

Why are ballots rejected?

Before going through the adjudication process, I didn’t realize how many ballots got rejected or the reasons for those rejections.

Ballots are typically rejected for one of three reasons:

- Over voting, where there are too many votes in a specific section. Know those sections that say “Vote for no more that 2 candidates?” Over votes are when you vote for more than that number. And it happens WAY more than you’d think.

- Stray marks, when the machine can’t properly read which marks go where. This can happen due to pen smudges, improperly filled bubbles (like check marks or Xs instead of filling them in), etc.

- Write ins trigger rejections so that adjudicators can properly review the names of the write in candidates, whether or not they actually filed their paperwork to be counted, and record those votes manually.

It’s the adjudicator’s job to figure out those issues and try to get them sorted in the software so that votes get counted.

Who adjudicates?

The cool part about adjudication (apart from helping people’s votes actually get counted) is that it’s a joint effort from the opposing political parties. Our adjudication team consisted of 12 people. Six of us from the Democratic party, six from the Republican side. Additionally, there were a number of election challengers watching over our shoulders, documenting our decision making process, ready to submit reports to their party in the case of disputes or shady dealings.

All of the adjudicators were Livonia citizens, ranging from their early 30s to their 60s. Livonia is an overwhelmingly white community, so I was sad to see only one person of color on the team. That being said, it was clear after 24 hours that we came from fairly diverse backgrounds, education, and vocations. Most of us had kids, which provided plenty of discussion opportunities, but we lived all over our city’s 36 square miles. There were a few educators, an IT professional, some retirees, an insurance agent, two marketers, a writer, an engineer, and even a former City Council member involved.

While I knew the Democrats (Hi, Chris, Carrie, James, Carl, and Jeff!) through my involvement with the Livonia Democratic Club, it provided the opportunity to get to know our Republican counterparts through the course of 24 hours.

What I Learned About Elections Through Adjudication

I have to say that, as consequential as the work is, it’s terribly boring most of the time. A lot of time is spent waiting for ballots to get processed and counted. And 24 hours straight of waiting around in uncomfortable chairs with no sleep can be very trying. But looking back at the experience with a few days’ hindsight has led me to a few lessons worth noting.

People Are More Civil Than You Think

Going into adjudication—especially with the 2020 political atmosphere in mind—I fully expected there to be plenty of disputes, arguments, and challenges throughout the day. Quite frankly, I expected to make a few enemies, too.

But what I made (as corny as it sounds) is a bunch of new friends. Everyone was very civil, respectful, calm and collected, and curious about each other, our experiences, and how they weigh into the adjudication process. Although there were a few times when I got annoyed by small comments from particular folks, it was an incredibly smooth process that not only allowed me to help my fellow citizens’ votes get counted, but connect with people I’d probably never meet in everyday life.

There’s Not Much Room for Voter Fraud

It also taught me that—despite what ill-informed people say—there is little to no room for voter fraud in the 2020 election. Simply put, there are just too many people paying attention for voter fraud to happen. Even with absentee ballots.

In Livonia, there were dozens of people watching the process and a very smart, capable, and tenacious City Clerk running it all. And, since all of those people chose to be there, you can count on them being at least a little more committed than the average citizen to the idea of free and fair elections.

Granted, this might be due to the fact that I live in a very privileged, relatively well-funded community, but I don’t see how there could be widespread voter fraud like Republicans—led by Donald Trump—claim on an hourly basis.

Anyone saying that election fraud is a concern in 2020 is doing so because they themselves haven’t worked an election. If they did, they’d shut up.

We Need Agreed Upon Principles

I firmly believe that the United States is in such dire straits because we’ve collectively lost our shared principles. Yes, a lot of those principles turned out to be bullshit completely undermined by things like economic inequality and systemic racism, but so much of our struggles are a result of polarization and our inability to agree on—what I would consider—some foundational principles like democracy, decency, science, equity, kindness, and doing no harm to others.

I said that I was surprised at how smoothly adjudication went. I think that is largely due to the fact that we agreed on some principles before we started looking at ballots. Before we even stepped into the room, one of the Dems, Christopher Lee, started a conversation about what should and shouldn’t count as a vote. Through discussion between both sides, we came to a collective understanding that bubbles filled in at least 20% would count as a vote, as well as some basic guidelines for determining the intent of the voter.

I absolutely believe that, if we had not spent the time agreeing on those guidelines, then we would have run into far more serious issues.

Everyone Should Work Elections If Able

Finally, my time adjudicating gave me an inside look at the election process. Before Tuesday, I didn’t realize how any of it worked beyond me filling in some bubbles, dropping a ballot in a box, and anxiously refreshing NPR.org to see the results hours later.

I didn’t realize how much work went into processing and counting those ballots. I didn’t realize that not everyone fills out bubbles the same way as I do. I didn’t realize how exhausting elections are for the people working their asses off to keep democracy running.

It honestly opened up a whole new world of understanding for me. And I think it would do the same for everyone else, too. I realize that not everyone can volunteer for elections for a host of reasons but, for those who can, I strongly encourage you to do so to learn more about how our country works and, more importantly, to help ensure that it keeps working and that every vote actually, truly, counts.

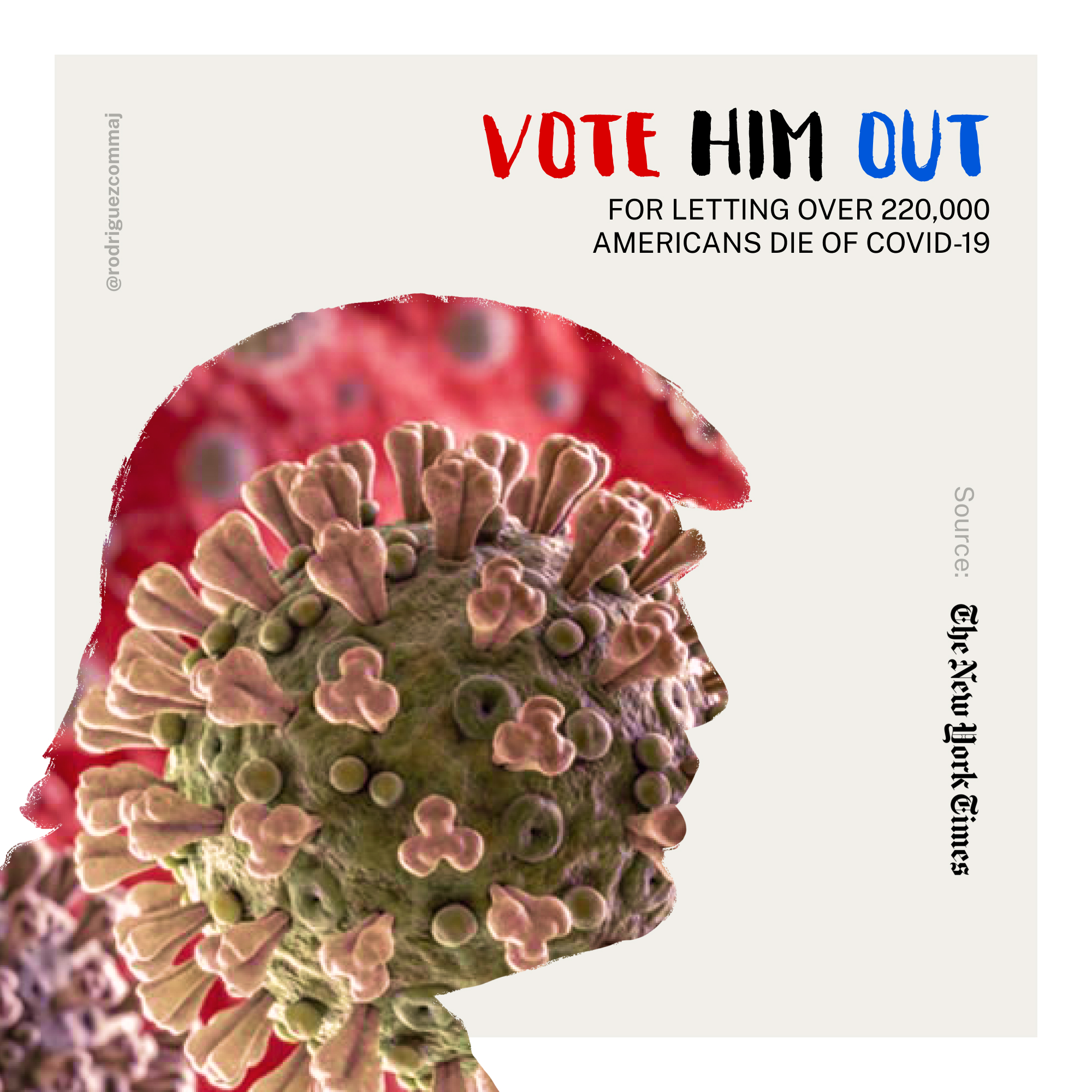

Vote Him Out

I’ve been helping out my local Democratic club lately by volunteering my design skills. Along with working on their websites and emails, I’ve designed a few GOTV mailers, too. Through volunteering, I seem to have rekindled my passion for designing things, which I don’t get to do too much anymore during my day job beyond slide decks and the like.

It seems that activism and graphic design trigger something good in me, which is why I spent some time yesterday putting together some anti-Trump social media graphics. While I shared them on Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook, I thought I’d post them here for posterity and in case anyone else wants to use them. Just credit me when you do, please.

Here’s the Dropbox link to all 10 images and a few of my favorites can be found below.

Do they feel just?

I’m just a simple email marketer but I have thoughts about the confirmation of Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court tonight.

A lot of anger at the shameful process, the blatant hypocrisy of the Republican-led Senate, the fear that comes with a conservative majority Supreme Court ruling in favor of policies driven by extreme religious views, and fear for all of the pain and damage this court is bound to inflict on minorities, LGBTQ+ communities, immigrants, the poor, and democracy itself over the coming decades…

The same feelings anyone with a shred of decency and any semblance of a functioning soul ought to be feeling right now.

But beyond that, one question keeps nagging me.

How does Amy Coney Barrett feel about everything?

Or Neil Gorsuch or Brett Kavanaugh? Do they feel proud of their “achievements”? Do they feel that the process was honorable? That they truly deserve and are worthy of the positions to which they’ve been appointed?

Do they feel just?

Although they are clearly oblivious to the needs and challenges of huge portions of the American population, I can’t imagine they are oblivious to the media. They have to be exposed to the protests and indignation so many people around the country have voiced. Even if they are insulated against all of that. Surely they’ve noticed the protests of Democrats in Congress?

How do they go about their work with that lingering over everything? Do they care at all?

Judges are referred to as “Honorable” when being addressed. But, especially in the case of Amy Coney Barrett, nothing about the nomination and confirmation process was—by any objective measure—honorable. How will that affect her work? Will she try to work towards the honor that is supposed to flow from the highest court in America? Or will she be corrupted by everyone’s anger at her appointment and rule based not on precedent but on vindication instead?

I’d like to think that—especially in the cases of Amy Coney Barrett and Brett Kavanaugh—that the Supreme Court will bring out the best in its Justices and that each one will comport themselves in a manner befitting their positions, but I don’t have high hopes. If they were truly honorable, they would have protested the disgraceful confirmation process instead of partaking in it. Amy Coney Barrett would have held Republicans to their own precedent set during Merrick Garland’s nomination or withdrawn from the nomination like dozens of her colleagues at Notre Dame urged her to do.

But she didn’t.

I’m sure there’s so much of the process that I don’t understand. So much of the inner workings of the judicial branch that are way above my head. After all, I am just a simple email marketer. But I do know that our elected representatives and those appointed by them have taken part in one of the most shameful and nefarious acts in recent history.

I’m feeling a lot of things tonight. But the most overwhelming feeling is that of disappointment in the system that is clearly failing all of us, on the right and the left.